Thomas Baines

Thomas Baines

By the mid 1820s prospects were brightening as they began to realise Albany’s grazing potential and began importing merino sheep. In the early 1830s when Port Elizabeth became a free port without import or export duties, sheep farming took off, encouraged by a rapidly escalating demand for raw wool in Britain, From Albany, sheep farmers spread into the neighbouring midland divisions while after the voortrekkers started leaving the Eastern Cape other settlers bought farms from them throughout the Eastern Cape. After Natal and the Orange River Sovereignty were annexed in the 1840s they also became sheep farmers in those territories. In the process, the settlers exerted an influence on South African economic growth out of all proportion to their numbers. They transformed the Cape’s essentially pre-capitalist agrarian economy and opened southern Africa up economically and commercially to the wider world.

While settler achievements benefited many South Africans, they also had unfortunate consequences. A growing labour shortage saw farmers turn to the Khoikhoi for labour but they soon regarded them negatively, arguing that those living on mission stations were being ‘ruined’ by missionaries who encouraged them to place themselves on an equal footing with whites and to resist their labour demands.

The settlers’ relations with the Xhosa were more ambivalent. Positively, the Xhosa were suppliers of goods, particularly ivory and skins, to the settlers. By the 1830s, growing trade between them was benefiting both white and black. Negatively, the newly-arrived settlers were not aware that in the frontier wars from the late eighteenth century, the Xhosa had been driven from the lands settlers now occupied. As settler leader, John Bailie, later commented, they settled on the frontier ‘unconscious of danger, little dreaming that we sat on a powder mine, which ultimately exploded with fatal effect’. They couldn’t comprehend Xhosa grievances or appreciate the destitution; land hunger and anger they were experiencing. More seriously, they did not realise that the Xhosa were determined to regain their lands. The result was growing conflicts between the two groups with Xhosa raiding cattle, at times killing individual settlers and the latter reacting.

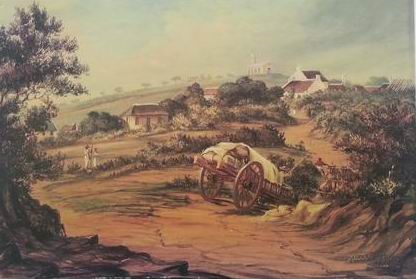

Xhosa Wars, Thomas Baines

By the 1830s, as sheep farming expanded and the economy boomed, so the merchants of Grahamstown who were investing heavily in sheep, and a new generation of frontier farmers that was growing up in need of land, were turning covetous eyes east of the frontier to the luxuriant grasslands held by the Xhosa, so much so that humanitarians and missionaries in the Western Cape accused them of wanting to dispossess the Xhosa of these lands.

Growing tensions led to the Sixth Frontier War when growing Xhosa desperation saw 20,000 warriors invade the colony in December 1834, burning settler homesteads and villages and driving off livestock. Although the Xhosa were driven back over the Great Fish River and the their lands to the Great Kei River were annexed to the colony, the British government subsequently disallowed the annexation, effectively blaming settler actions for having left the Xhosa no option but to go to war. The war and its aftermath were traumatic for the settlers who now lived constantly afraid of being attacked and concerned about the safety of themselves, their stock and property. As settler John Mitford Bowker eloquently described their lives: ‘the anxieties – the watchings – searchings – dogs barking’. Many became embittered and hostile, seeing themselves rejected by the British government and the Cape administration and regarding the Xhosa as a cunning and dangerous enemy. In the process they were beginning to forge a frontier identity that was both separatist and racist and which saw them emphasise their role as a civilized post on a dangerous frontier.

High Street, Grahamstown

In 1844, with all that they had been through in the previous 25 years and were to experience in the future, and this included another two frontier wars between 1846 and 1852, the settlers felt that they had good reason to celebrate the settlement’s silver jubilee. Their arrival in the Eastern Cape might not have planted the closely-knit agricultural community that Lord Charles Somerset had envisioned to act as a buffer against Xhosa incursions. But what it had done was establish a self-contained British community with a cohesive and distinct identity.

In 1844, with all that they had been through in the previous 25 years and were to experience in the future, and this included another two frontier wars between 1846 and 1852, the settlers felt that they had good reason to celebrate the settlement’s silver jubilee. Their arrival in the Eastern Cape might not have planted the closely-knit agricultural community that Lord Charles Somerset had envisioned to act as a buffer against Xhosa incursions. But what it had done was establish a self-contained British community with a cohesive and distinct identity.

A settler family, 1820 Settlers National Monument

Many had come to love and identify with their new home and a strong sense of belonging to the Eastern Cape was beginning to evolve, particularly amongst those who remained on the land.

While retaining their British identity and loyalty, the settlers had given southern Africa a permanent, cohesive and distinctive English-speaking population, one which was identifying itself with South Africa and, the ultimate sign of belonging, was already beginning to speak with a distinctive South African accent. They were becoming a people who were, for good and ill, to have a profound effect on South Africa’s future and on the relationships between English and Afrikaner and between white and black.

Thomas Baines

Thomas Baines